WilkinsonEyre director Sébastien Ricard reflects on the long and complex journey to restore Battersea Power Station, exploring how flexibility, mixed use and deep respect for heritage were essential to transforming a near-derelict industrial monument into a resilient piece of city.

Credit: Charlie Round-Turner

Drawings

WilkinsonEyre

There were many attempts to redevelop Battersea Power Station (BPS) in the past. What lessons did you learn from them?

When we first began working on the project, it was obvious that we were stepping into a legacy shaped by repeated setbacks. The scale of restoration required was enormous, and no scheme could succeed unless it generated sufficient value to fund the transformation of a Grade II* listed industrial monument.

Crucially, the project could never rely on a single land use. A building of this magnitude requires a carefully curated mix: commercial, retail, workplace, leisure, and residential, to create both social and economic sustainability. Our core lesson from earlier attempts was that only a carefully crafted mixed-use strategy could unlock the resources necessary to save the building.

Why did no other developers want to touch it?

Quite simply, the task was mammoth in every conceivable way. By 2012, the building had reached a state of almost dilapidation. Some of the main walls were listed as dangerous structures in the local building control register, the main roof above the Boiler House had collapsed, so what remained was a vast, contaminated industrial shed with little natural light. This was extremely challenging to adapt without major intervention. All of this existed within the strict constraints of a Grade II* listing and there was no underground station – so it came with multiple barriers.

Multiple teams had tried and failed, and with every passing year the building’s condition worsened. Ultimately, it took a group with extraordinary vision, patience, and financial resilience to take on what was, at the time, a significant gamble. The investment has been transformative, not only for the building, but for this part of London.

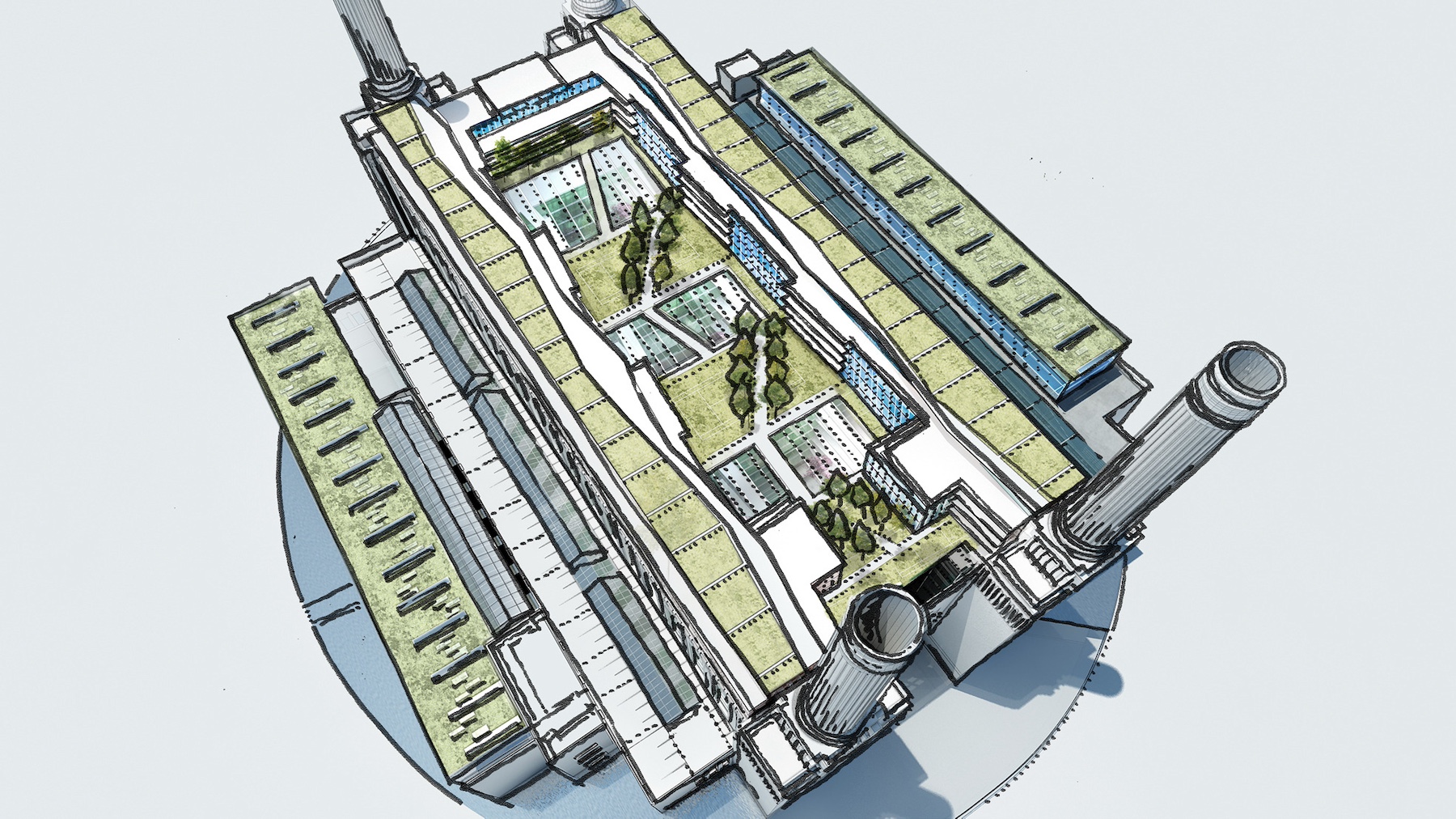

Sketch axonometric view from above.

You had three weeks to submit a proposal, for which you included a range of freehand sketches describing design intent. What did those sketches look like? And what did you want them to describe in particular?

My first visit to the building was overwhelming. The sheer scale was extraordinary. With only three weeks to develop a submission, our ambition was not to present a full design but to articulate a clear approach.

The sketches were deliberately loose, describing a philosophy and attitude to the building, rather than a finished proposal. Their intention was to respect the magic and monumental scale of the heritage architecture while imagining how the building could operate as a functional, sustainable component of the city of London. One where visual clues – glimpses of the chimneys or the brick – would root you in the building.

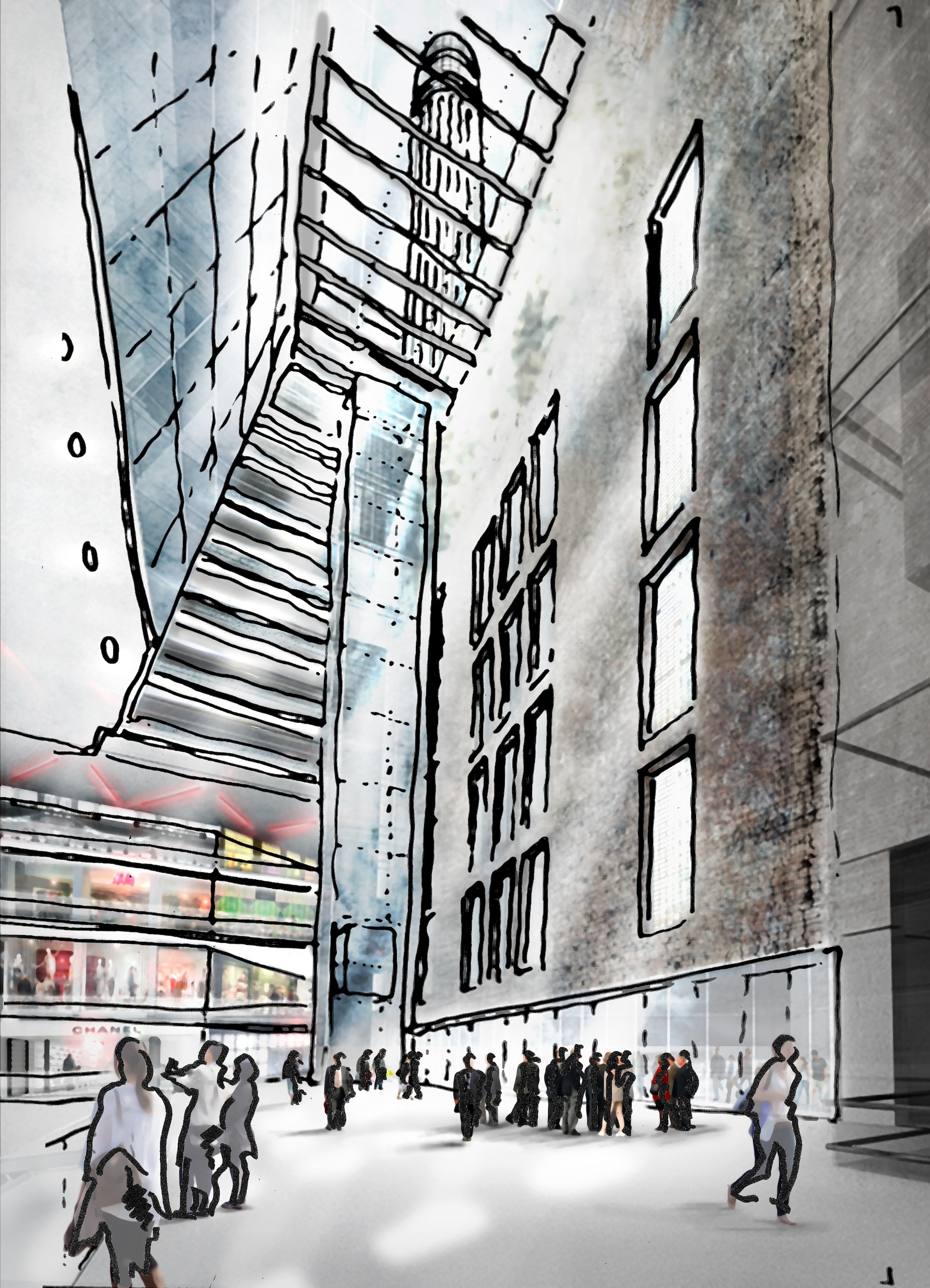

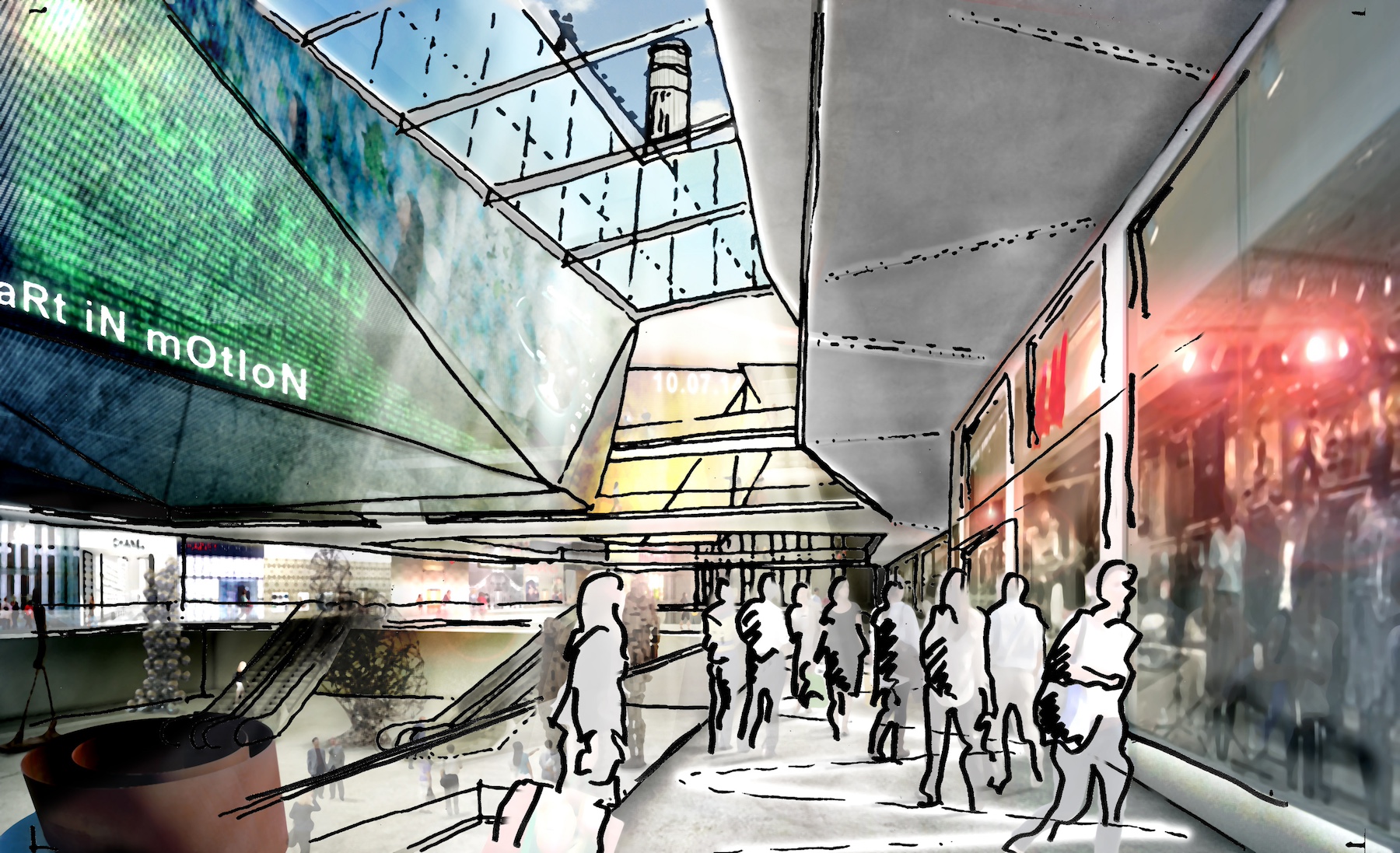

Competition sketch: south entrance atrium.

The South Entrance sketch, for example, proposed a full-height atrium that revealed the existing façade with minimal restoration, offering glance views to the chimneys while keeping new interventions set back from the historic fabric. The intention was to preserve the building’s industrial character and ensure that, wherever you are within the Power Station, you maintain a visual relationship with its original structure.

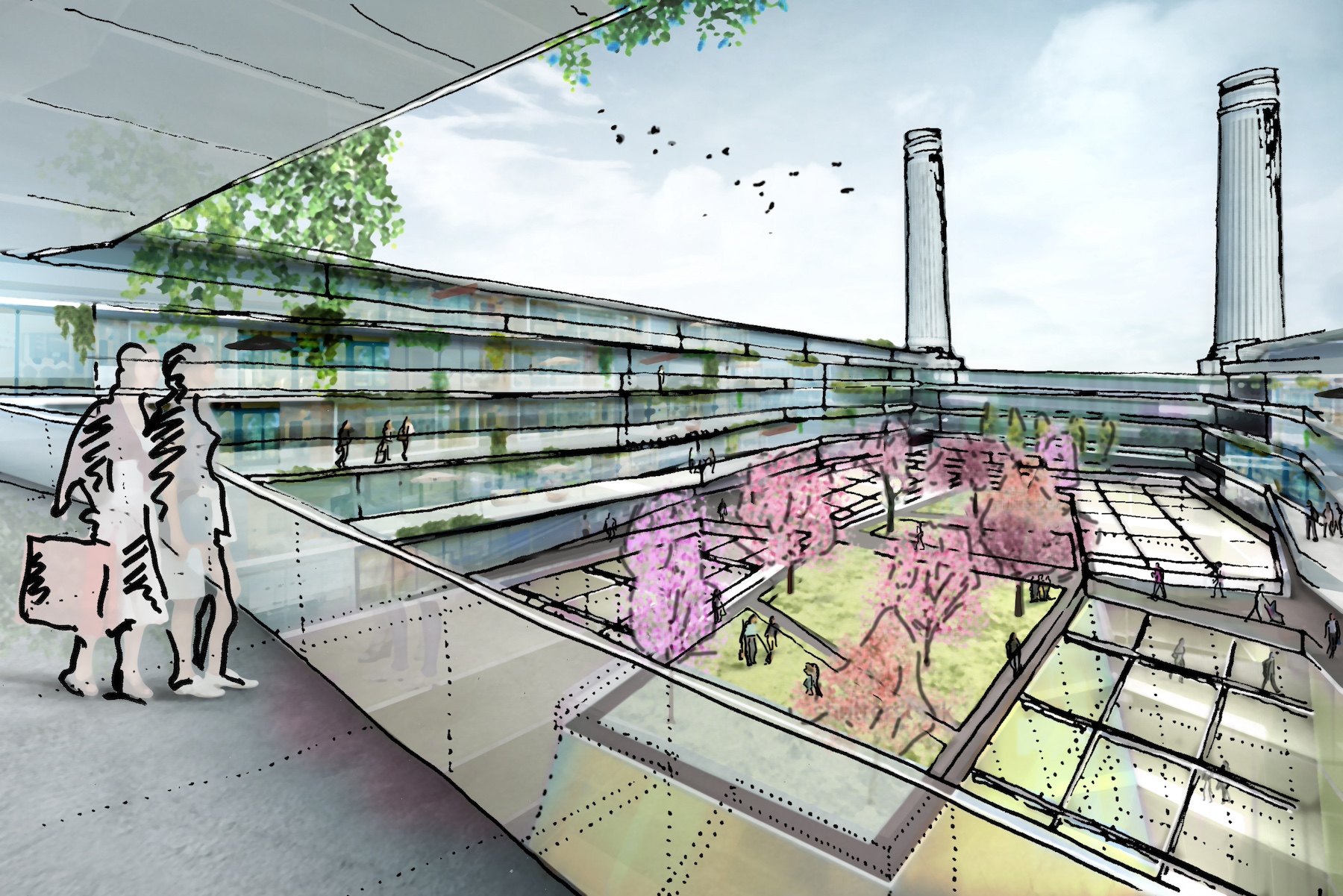

Sketch of the residential view over the roof.

The roof sketch explored the idea of inhabiting the roofscape, around 150m by 150m, by introducing community and private gardens rather than simply reinstating these volumes and a conventional roof.

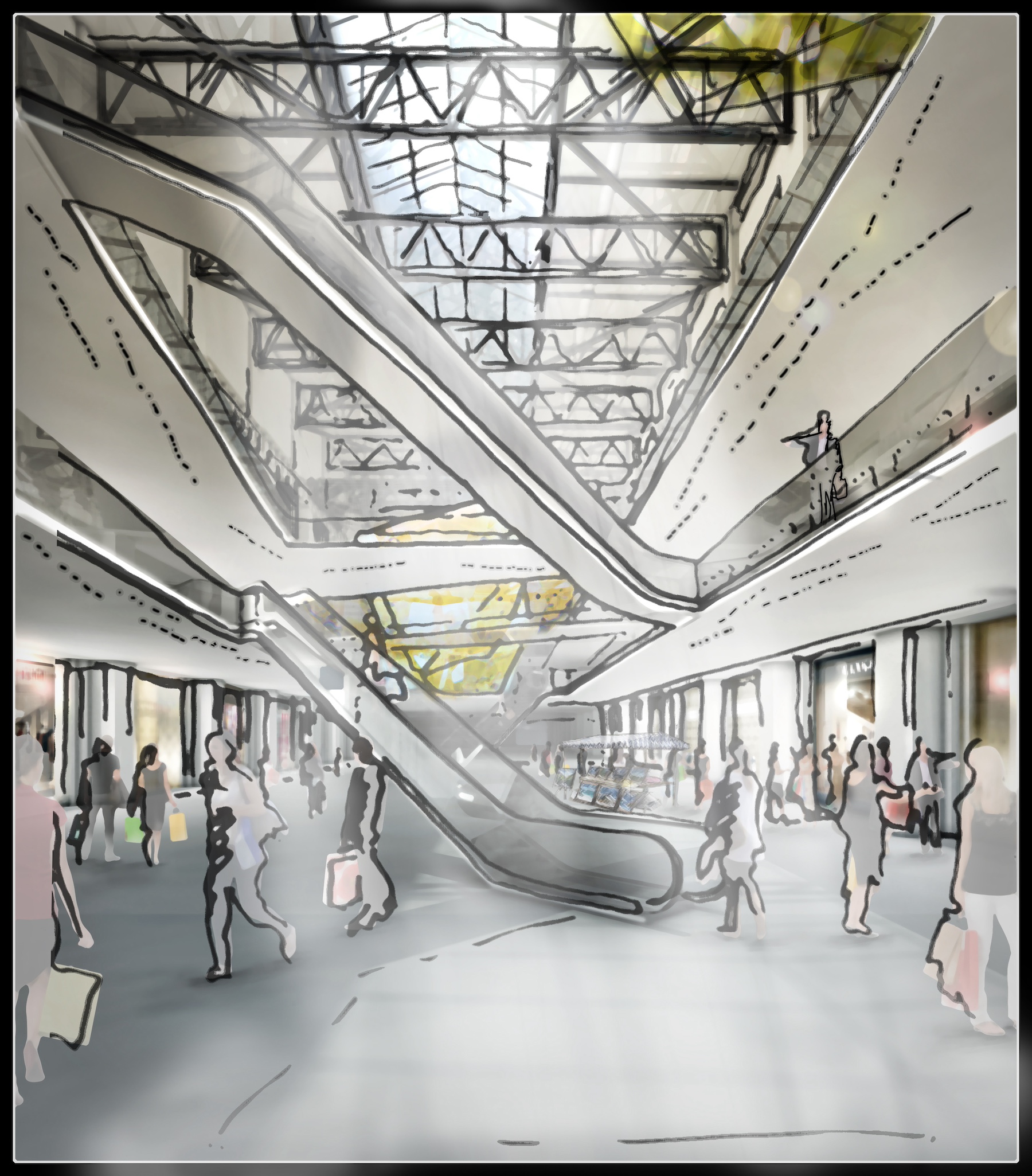

Sketch of the Turbine Hall interior.

The Turbine Halls sketch demonstrated how retail could be accommodated while preserving the remarkable scale and perspective of the space through the careful integration of lightweight bridges and escalators.

Sketch of the proposed office spaces.

The office concept sketch showed how internal atria could be carved into the deep floorplates to bring natural light into the centre of the building, while exposing the original external brickwork from within. The aim, again, was to maintain visual connection with the historic fabric wherever you are in the building.

Sketch of the proposed retail area.

When working on such a large building, there are many unknowns. What did you discover?

On a building of this age, scale, and complexity, unknowns were inevitable, but even then, several discoveries exceeded expectations: Contamination levels were significantly higher than anticipated; large areas of the faience wall lining in the Turbine Halls were in a worse state than anticipated, requiring extensive mechanical fixing to render them safe; all four chimneys required complete reconstruction as internal reinforcement was exposed and beyond salvage; and the East Wall of the Boiler House was designated a dangerous structure, ultimately concluded it was beyond repairs and had to be rebuilt.

These examples represent only a fraction of the daily discoveries uncovered across a 12-year programme. It is impossible, and unrealistic, to fully understand a building of this complexity at competition stage; only in-depth, structural or condition surveys reveal its true state.

How did your initial proposals factor in the financial sustainability of the project? And did they accommodate changes to the proposals?

From the outset our proposals demonstrated how a high-density mix of uses could be woven into the existing building fabric. We tested these initial ideas with the client, local authorities, and heritage bodies, receiving positive feedback early on. This provided confidence that the scheme could support a robust financial offer for the project’s funders.

The brief continued to evolve in response to market conditions and anchor tenants – most notably, the arrival of Apple. But because our approach was based on a flexible kit of parts rather than rigid architectural prescriptions, we were able to adapt: the office component shifted from a multi-let to a single-tenant strategy; retail unit footprints were adjusted to accommodate specific operators; residential layouts were refined to suit varying buyer preferences; and flexibility was not an afterthought – it was a fundamental principle. For a project of this scale and complexity, adaptability is essential from conception to construction.

Brickwork up close. (Credit: Peter Landers)

How did you source and match the brickwork of the original building?

Sourcing and matching the original brickwork was a meticulous process. Contemporary advertisements and trade journals proved invaluable, as many manufacturers were keen to be associated with the Power Station when it was built and frequently branded their products. Accrington’s ‘NORI’ bricks and the London Brick Company’s ‘LBC’ Flettons, for example, could be identified from these markings and archival sources.

However, identifying the original suppliers was only the beginning. We then had to determine which of those manufacturers could still produce bricks that matched the historic material. Even where companies remained in operation, their current products were rarely identical. For Turbine Hall A, it took several rounds of testing with Ruabon in Wales to achieve an accurate match to the original buff-coloured bricks.

Internally, the predominant brick was the Fletton, but the modern metric version was not an adequate resemblance to the imperial-sized bricks of the 1930s. Northcot were able to produce a near-perfect imperial match, allowing us to repair internal walls while maintaining the original bonding patterns and jointing. Their handmade process also enabled the production of small batches of ‘specials’ – such as pier caps, voussoirs and even new bespoke pieces designed to provide discreet ventilation or bat roosts – ensuring that both restoration and new interventions were authentic.

How did you accommodate the local Peregrine Falcon? Were you aware of the bird species calling the BPS home?

We worked closely with BPSDC’s Peregrine Expert, David Morrison of London Peregrines, to design a permanent home for the birds that had occupied the Power Station for over 20 years. Peregrine nests are typically simple boxes, but as with much of the project the challenge lay in integrating this modest structure discreetly within the historic fabric while ensuring the birds remained accessible yet largely undisturbed.

During construction, a 50-metre-high temporary steel tower provided a safe nesting site for six years. Their permanent home is now located in the North-East tower, accessed discreetly from the rear of one of the office WC blocks, complete with CCTV monitoring and a trap to allow cleaning when required. It’s fair to say that the peregrines now enjoy some of the finest accommodation in the entire development.

Bracing keeps the historic façade in check inside the south atrium. (Credit: Backdrop Productions)

Is there room for the BPS to continue to adapt in the future?

The Power Station has been designed to continue adapting over time. In the Turbine Halls, for example, retail units are framed by portal structures that allow shopfronts to be reconfigured without impacting the listed fabric. The office floors are conceived as large, flexible plates that can be subdivided in multiple ways, with soft spots reserved for the future integration of stairs. Residential units can be combined if required, and both the event space and food hall are intentionally loose-fit volumes capable of being reorganised when leases end.

In practice, the building is already adapting on a weekly basis. Infrastructure for pop-ups and temporary events is woven into both the architecture and the surrounding public realm. The exhibition beneath the Chimney Lift has recently been reworked in response to visitor feedback, and BPSDC’s year-round programming has transformed the public spaces into everything from an ice rink to a running track. Most importantly, it’s wonderful to see the building open, animated, and well used by both local residents and visitors.

What lessons have you learnt from the project?

This project is unique in its scale, complexity, and range of activities, making it difficult to compare with any other project. What it taught us above all is that delivering a project of this magnitude depends on teamwork:

- Drawing on the best skills and expertise across every discipline.

- Working with people who consistently put the project first, often ahead of their own interests or those of their organisation.

- Prioritising problem-solving over contractual positioning; the challenges were numerous, but resolving them was rewarding and gratifying.

- Accepting that a project of this nature cannot be fully fixed at planning stage. The sheer volume of discoveries meant the design had to evolve continuously.

- Recognising that a mixed-use scheme of this scale must remain responsive to market shifts, requiring architectural flexibility.

- Understanding that good architecture must be underpinned by financial viability; creating value is what enables investment in quality.

- Embracing the quirks and imperfections of the existing fabric. By working with, rather than against, the nuances of a building never intended for these uses, we were able to create architecture with a distinctive and unexpected delight.

Credits

Client

Battersea Power Station Development Company (BPSDC)

Architect

WilkinsonEyre

Structural engineer

Buro Happold

M&E consultant

Chapman BDSP

Construction manager

MACE

Lighting designer

Spiers & Major

Residential apartment designer

Michaelis Boyd

Project manager

Turner & Townsend

Cost consultant

Gardiner & Theobald

Planning consultant

DP9

External landscaping

LDA Design

Roof garden design

Andy Sturgeon

Conservation consultant

Purcell

Source: Architecture Today