Housing Atlas

A compendium of the best housing schemes built across Europe in the 20th Century is an invaluable resource for architects seeking solutions to the current housing crisis.

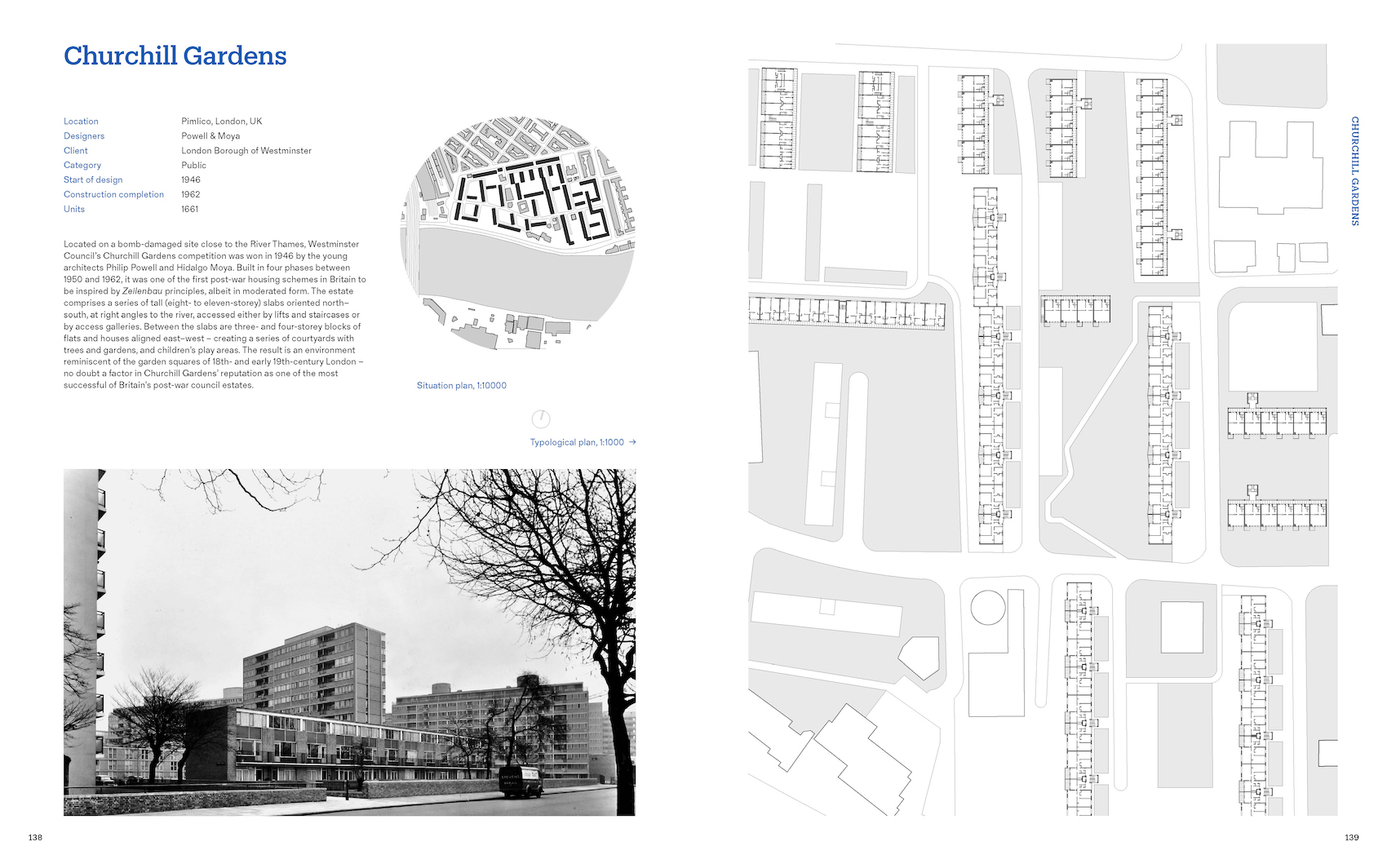

Double page spread devoted to Powell & Moya’s Churchill Gardens, London, completed in 1962. All projects have been painstakingly redrawn to the same graphic standard.

Words

Kenneth Frampton

It is hard to imagine a more opportune time in which to publish a compendium on housing, given our current escalating homelessness and our chronic maldistribution of wealth, both of which give an implicitly political significance to this encyclopaedic study. For by now it is self-evident that we will never arrive at an ecologically valid pattern of land settlement as long as we persist with our laissez-faire, inherently wasteful automotive suburbanisation. At a moment of considerable pedagogical confusion in our architectural schools, not to mention the profession itself, this mammoth didactic volume arrives to remind us of the way in which the habitat as a whole remains the ultimate responsibility of environmental designers. This magnum opus is not so much a book to be read as it is a document to be worked through in our schools in order to deconstruct, as it were, the full ramifications of its content; i.e. the way in which each successive housing scheme, arranged in chronological order for the entirety of the century, evokes comparison to other assemblies of a similar genre and even to other equally canonical examples that are not accounted for in its pages.

This study is such a tour de force as to render a review of limited length virtually impossible. The culmination of a long-term academic, intercultural collaboration between Orsina Simona Pierini of the Politecnico di Milano, Carmen Espegel of its parallel institution in Madrid, Dick van Gameren of TU Delft and Mark Swenarton of the renowned University of Liverpool School of Architecture, this magnum opus is not only the consequence of years of painstaking research and debate but also of the equally overwhelming task of redrawing all the archive material to the same hard-line graphic standard, consistently representing the works at the scale of 1:10,000 for the situation plans, 1:1,000 for the general layout, and 1:500 or 1:250 for the dwelling units. The net result is the precise documentation of 87 housing schemes, chronologically arranged for the span of the century, beginning with Parker and Unwin’s Hampstead Garden Suburb of 1905 and ending with Herzog and de Meuron’s infill housing realised in the Rue des Suisses, Paris in the year 2000.

Perhaps the most striking revelation of this study is the extent to which the expansion of the continental European city in the second half of the 19th Century and the first quarter of the 20th was invariably predicated on perimeter block housing where the new addition conformed to the format and modular dimensions of the surrounding infrastructure made up of similar blocks, thereby inevitably producing a tight fit between the new work and its civic context. It is this principle that is the context for the brilliant Neo-Wrightian Papaverhof estate designed by Jan Wils and realised in Den Haag between 1919 and 1921, and the equally masterful Kiefhoek estate built in Rotterdam to the designs of JJP Oud over the years 1925-30. We will encounter something similar in Spain, where we find Secundino Zuazo’s Casa de las Flores, built as a double-layered perimeter block in Madrid in the early 1930s, echoing the square format of the surrounding infrastructure. This civic tradition will be so strong in Spain as to persist into the mid ‘80s with Oriol Bohigas of MBM Arquitectes inserting a perimeter block into the residential fabric of the Catalan city of Mollet del Valles.

Double page spread devoted to Atelier 5’s Siedlung Halen, outside Bern, Switzerland completed in 1961.

Perimeter housing around a central court will continue to be adopted as the typical city building block in continental Europe until the mid ‘20s, as is particularly relevant in the work of the Danish architect Kay Fisker. Thereafter it will be replaced by the normative ‘open city’ paradigm of the Zeilenbau system, comprising repetitive parallel rows of mid-rise, ‘walk-up’ terrace housing, all of the same east-west orientation, and of the same height, depth and standard distance apart. As it happens, this typology would exhibit just those qualities favouring the industrialisation of buildings which Walter Gropius will be the first to exploit through his pioneering use of a tower crane mounted on rails, in the realisation of his Törten Housing, built outside Dessau in 1926.

Henceforth, housing interventions will tend to become singular free-standing objects, suspended within the space-endlessness of the seemingly limitless metropolitan domains, thereby spontaneously dissolving the traditional boundaries between town and country; a process that had been anticipated by Ebenezer Howard, in his famous garden city thesis of 1898. This already accounts for the topographically inflected Zeilenbau form of Ernst May’s Romerstadt estate built on the outskirts of Frankfurt in 1927, where the parallel row house terraces assume a gently curved form in plan in order to accommodate the course of a nearby river. In retrospect one is astonished by the extraordinary variety that housing will assume over the course of the century, ranging from free-standing communal slab blocks, such as Moisei Ginzburg and Ignatii Milinis’s Narkomfin Building of 1929, the one extant Soviet Constructivist Dom- Kommuna which will be the ultimate inspiration behind Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, Marseille (1946-52). Equally impressive as an all-encompassing free- standing single block was the monumental microcosm of Karl Ehn’s one-kilometre-long Karl-Marx-Hof (1926-1930), the ‘flagship’ block, so to speak, of Red Vienna’s working- class perimeter blocks. Serving the same class, but totally diminutive by comparison, was the Justus Van Effen blok (formerly known in the ‘60s as Spangen), the claim to fame of which, then as now, was its pioneering use of an elevated street, circumnavigating the interior of the four storey block at mid-point. It is this feature that will ensure its influence on the British Brutalists, culminating in the gargantuan Park Hill estate in Sheffield completed to the designs of Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith in 1961.

This happens to be the same date as the completion of its antithesis, namely, Siedlung Halen, built outside Bern, Switzerland, to the designs of Atelier 5, a work evidently derived from Le Corbusier’s reinterpretation of the coastal vernacular of the Mediterranean; the Roquebrune low-rise housing that he projected for Cap Martin in 1948. This shift into ‘mat-building’, capable of engendering innumerable labyrinthine routes through its interstitial fabric will make itself manifest in different ways throughout the late ‘50s and early ‘60s in Jorn Utzon’s Kingo Courtyard Houses (1959), in Michael Neylan’s Bishopsfield housing, Harlow (1961-67), in Neave Brown’s Fleet Road housing for Camden (1966) and in Giancarlo De Carlo’s Matteotti Village, Terni (1969-75).

Of the four introductory essays written by the organisers of this immense body of comparative research and documentation, only that by Mark Swenarton engages with the demise of housing under the auspices of Neoliberalism with its well-known aversion to any kind of planned economy. It is not without significance, however, that his essay will close with the re-emergence of the street as a space of public appearance in the low-rise, high-density middle-class Accordia housing estate, realised outside of Cambridge in 2002, to the designs of a consortium of architects led by Feilden Clegg Bradley.

AT Editor2024-04-19T14:37:01+00:00

Related Posts

Source: Architecture Today